From tea in a British buffet car, to luxury dining on the Trans-Siberian Express, eating on trains can be a true culinary adventure.

By Sharon Hudgins

Photos by the author

I grew up riding trains across America just before the era of classic passenger service ended on the railroads and before Amtrak was a gleam in the government’s eye. Later I rode trains all over Europe from northern Scotland to central Italy, from the coast of France to the plains of Hungary. And in Russia I’ve logged nearly 40,000 miles on the legendary Trans-Siberian Railroad, crossing the continents of Europe and Asia between Moscow and Vladivostok several times.

That’s also a lot of dining on trains, snacking on railroad station platforms and eating at station buffets.

DINING ON BRITISH TRAINS

I remember riding first class on British Rail across England and Scotland many years ago, when smartly uniformed stewards served tea in your private train compartment, first spreading a starched white cloth on the little table under the window, then pouring the hot brown brew from a silver-plated teapot into a porcelain cup (with milk added first or last depending on where you stand on that contentious issue). A small plate of sweet biscuits (cookies, in American English) always accompanied the tea. What a civilized way to spend a morning or afternoon, sipping tea, nibbling on biscuits, and watching the British countryside roll by outside the window.

Morning coffee and afternoon tea were included in the price of the ticket. But like many travelers on trains all over the world, I often chose to save money on meals by purchasing food from station vendors to eat on the train. Once in a while, however, I’d splurge on a meal in the dining car, luxuriating in the “white-tablecloth service” and the selection of foods that were so different from those I’d eaten on American trains.

(left) Conductor on the Cheltenham Flyer, historic steam train of the Gloucestershire Warwickshire line of the British Great Western Railway.

Alas, in 2011 contemporary trains in Britain did away with the last of their full-service dining cars, replacing them with airline-type meals served at the seats of first-class passengers and microwaved snacks sold in the buffet car for everyone else. But there’s hope for the future: In 2013 the First Great Western Railway re-introduced full-service “Pullman dining,” with fine wines and locally-sourced foods, on the UK’s only remaining regularly scheduled train with a real restaurant car. But, strangely, the dining services don’t operate on weekends or public holidays!

However, special tourist trains in Britain, including many historic trains, still provide a range of enjoyable culinary experiences. Recently I traveled through England’s lovely Cotswolds countryside on the historic Cheltenham Flyer, a 1930s-era steam train that chugs along the Gloucestershire Warwickshire branch of the Great Western Railway, which has been operating trains in western England since 1838. The train included a restored 1950s “buffet saloon car” whose menu offered Scotch eggs, pork pies, bacon rolls, homemade flapjacks and homemade cakes, along with a range of hot and cold drinks, alcoholic and non-. At certain times of the year, the historic trains running on these rails also offer special culinary tours, from Fish & Chips Specials to Ale & Steam Weekends (sampling 24 real English ales) to Luxury Pullman Style Dining Experiences with multi-course meals served on china plates, accompanied by wines poured into crystal glasses.

CONTINENTAL RAILROAD DINING

The railroad dining experience on the European continent varies from country to country, type of train, and distance of travel. Some local trains have no dining facilities at all. Others have only a small snack bar or buffet, or vendors who come through the train with a cart stacked with packaged foods and canned drinks. Some have a full-service dining car, with a menu featuring multi-course meals and a selection of wines. If fine food and white-tablecloth dining are an important to you on a rail journey, then you need to seek out the trains that have a separate dining car and well rated menus.

For the ultimate in Old World luxury train travel (and dining), book a journey on the Venice-Simplon Orient Express, a modern revival of that classic train, which operates several tours of different lengths between London and Istanbul. The trains also feature three beautifully restored dining cars from the 1920s, with haute cuisine to match. Wear period dress to dinner, and you’ll feel like you’ve stepped back in time into an Agatha Christie novel.

Who could resist the special Swiss Chocolate Train that takes you on a day trip to a cheese-making factory, Gruyères Castle, and the Cailler-Nestlé Chocolate Factory in Broc for cheese and chocolate tastings at those stops? Travel in a vintage Pullman Belle Epoque-era train car or in a sleek, ultramodern panoramic car with large windows for viewing the Swiss Alps, the vineyards surrounding Montreux and the medieval town of Gruyères along the route. Bring along a shopping bag and leave your calorie counter behind.

Don’t overlook the foods to be found inside train stations, too. If you don’t want to spend big bucks to travel on a luxury train but you still like to eat well, you’ll find plenty of choices at many of Europe’s train stations, particularly those in the larger cities. I’ve been especially impressed with the train station buffets and take-out selections at major Swiss, German and French stations, as well as those in capital cities such as Budapest and Madrid. But for the ultimate in elegant, nostalgic, train-station dining, don’t miss the beautifully restored Le Train Bleu (The Blue Train) restaurant in Paris’s Gare de Lyon—a Belle Epoque-style restaurant with a pricey French menu and a gorgeous decor to match.

DINING ACROSS CONTINENTS

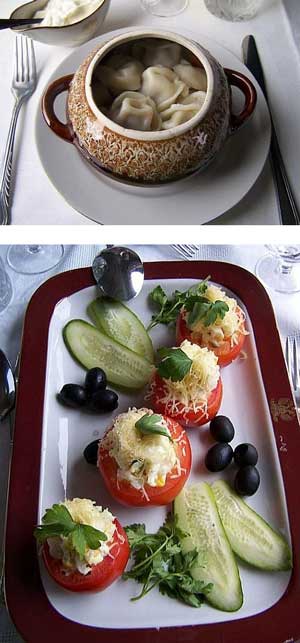

Finally, for the travel adventure of a lifetime, board the British-owned, Russian-operated Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express whose route covers nearly 6,000 miles between Moscow and Vladivostok. Almost half that distance is on the European side of Russia, from Moscow to Kazan to the Ural Mountains. Each comfortable cabin on this luxury train has its own private bathroom. And three times a day, professional chefs in the a fully equipped kitchen car turn out freshly cooked meals featuring regional specialties, all served in an elegant dining car designed to evoke the Golden Age of train travel. During the 12-day journey across Europe and Asia, the menu is different at every meal except breakfast. On this longest train trip on earth, you’ll have plenty of time to enjoy the best of Russian cuisine and international wines while watching the fascinating changes of scenery outside the dining car windows.

So wherever you travel by train in Europe, enjoy the experience of dining on (and off) the diner. It’s a great way to taste a wide variety of regional foods and expand your culinary and geographic horizons at the same time.

For more information see:

- British Great Western historic train travel in the Cotswolds

- British First Great Western contemporary railroad dining facilities

- Rail Europe on-board dining facilities in several countries

- Swiss Chocolate Train

- Venice-Simplon Orient Express

- Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express

- Luxury dining on the Trans-Siberian Railroad