By Sharon Hudgins

Photos by the author

Since the Middle Ages, the English university town of Oxford has been attracting scholars hungry for knowledge. Today it also draws hordes of tourists hungry to see its Gothic colleges, top-notch museums, colorful gardens, lively student hangouts and cozy pubs.

We all know that sightseeing is a strenuous activity that boosts your appetite. And Oxford offers plenty of places for filling empty stomachs as well as hungry minds. In this historic “city of dreaming spires,” you’ll find something to suit every taste, from traditional English pork pies to sushi rolls, from falafel sandwiches to chocolate fudge, from goat cheese pizza to the best of British cuisine.

FAST FOOD

In a town full of students, there’s no dearth of fast-food joints. Skip the inevitable McDonald’s and KFC, and head for the simple eateries offering more typical British fare. The West Cornish Pasty Company on Cornmarket Street sells very good versions of these traditional English turnovers with a selection of savory fillings. Many other takeout places, including supermarkets, offer fresh sandwiches stuffed with prawns, sliced cucumbers or egg salad, perfect for a picnic on a hot summer day. And food trucks parked around the edges of the central city cater to eaters on the go, selling a variety of takeaway dishes from India, Pakistan and the Middle East, as well as British standards such as “toad-in-the-hole” (succulent sausages baked inside Yorkshire pudding batter).

OXFORD COVERED MARKET

Opened in 1774, Oxford’s venerable covered market is one of the city’s most popular tourist attractions. In addition to its fruit, vegetable, meat, fish and cheese stores, it includes several little shops selling cooked foods to nibble on site or take away. Choose from an eclectic group of eateries: a “Brazilian Cheeseball” stand, a “Sooshe” bar, Nash’s Oxford Bakery, David John’s traditional butchery and meat pie shop. An especially popular place is Pieminister, which offers several kinds of freshly made, double-crust, meat or vegetable pies served with “mash” (mashed potatoes), “groovy” (gravy) and “minty mushy peas” (just what they sound like).

Traditional English pie with gravy at Pieminister in the Oxford Covered Market

PUB GRUB

Oxford’s historic pubs are famous as much for their denizens as for their beer. You can quaff a pint of British bitter or English ale in the same spots where Thomas Hardy, Lewis Carroll, J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Graham Greene, the fictional Detective Inspector Morse and many other Oxford luminaries wet their whistles. Pubs also serve food, sometimes the best bargains for a full (and filling) meal in Oxford. Typical dishes include fish-and-chips (battered-and-fried fish filets with French fried potatoes), Scotch eggs (hard-boiled eggs surrounded by sausage meat and deep fried), “Ploughman’s Lunch” (thick wedges of cheese and a slice of ham served with apple slices, sweet pickle relish, bread and butter) and “jacket potatoes” (aka baked whole potatoes, in their skins) with a choice of toppings: Cheddar or blue cheese, pork and beans, sautéed mushrooms, even meaty (or vegan beany) chili.

(left to right) Food shop inside Oxford Covered Market; Cottage loaves for sale at the weekly Oxford open-air market; The Bear, one of Oxford’s famous traditional old pubs

Purchase a guide to Oxford’s pubs at the Visitor Information Center on Broad Street or at many bookstores. You can also buy a postcard depicting 36 classic pubs for an “Oxford Heritage Pub Crawl.” My own favorite pubs include The Bear, The White Horse Inn, The Rose and Crown, The Lamb and Flag, The Eagle and Child and The Head of the River.

Head of the River, a favorite Oxford pub with a large beer garden

TEA & SWEETS

You can’t visit England without having afternoon tea—a civilized sit-down with a pot of freshly brewed tea, finger sandwiches and baked goods (such as scones with jam and clotted cream, and a selection of scrumptious cakes). Several cafes advertise afternoon tea with a sign in their front windows. Some upscale restaurants also serve formal “teas” between 3:00 and 5:00 p.m. For an elegant experience in the grand old English manner (with prices to match), “take tea” in the drawing room of the Macdonald Randolph Hotel across from the Ashmolean Museum.

If you just need to satisfy your sweet tooth, stop in at Nash’s Bakery in the Covered Market for traditional British pastries, or head for the Fudge Kitchen on Broad Street, which sells more than 20 different flavors of fudge made fresh daily.

Handmade fudge at the Fudge Kitchen on Broad Street

RESTAURANTS

Oxford has a wide range of full-service restaurants to fit any budget. Local foodies especially like Brasserie Blanc, on Walton Street, owned by one of the most respected chefs in Britain, Raymond Blanc; Jamie’s Italian, on George Street, one of a chain owned by another famous chef, Jamie Oliver; Gee’s, an Oxford landmark on Banbury Road; The Old Parsonage, on Banbury Road; and Magdalen Arms, a “gastropub” on Iffley Road. Look for fixed-price lunches of two or three courses for approximately £12 to £17 per person. Some restaurants also offer the same deal for “early supper” between 5:30 and 7:00 p.m.

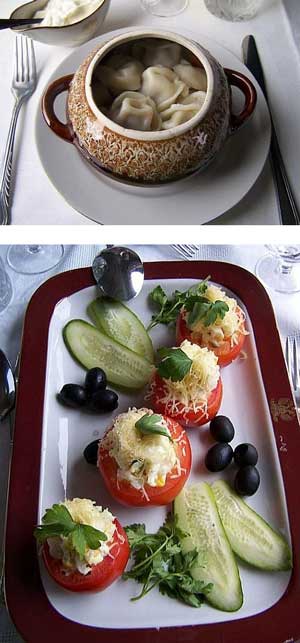

Luncheon appetizer at Gee’s Restaurant on Banbury Road

Oxford has no lack of Asian restaurants, from Indian to Chinese, Japanese, Thai and “Asian fusion.” Popular Asian eateries include My Sichuan, Shanghai 30’s, Majliss, Saffron, Chiang Mai Kitchen and Wagamama.

And for your big splurge, drive out to Raymond Blanc’s Le Manoir aux Quat’ Saisons in Great Milton, just seven miles east of Oxford. This fine restaurant has garnered two Michelin stars and won many other culinary accolades. You’ll be tempted to stay overnight at the historic manor house, too. Just be sure to make reservations well in advance, for both the hotel and restaurant. Dining there is an experience you’ll never forget.

● Travel tip: The Oxford Visitors’ Guide, a handy booklet that costs only £1 at the Oxford Visitor Information Centre (15/16 Broad Street), contains a short history of the town, a map, a brief description of the colleges and their opening times, Top 10 Things to Do, a self-guided walking tour, and vignettes of Oxford’s most famous characters. Also pick up a free copy of the Oxford Restaurant Guide booklet.

● Online travel information: www.visitoxfordandoxfordshire.com/travel-information/Tourist-Information.aspx

Additional restaurant information online:

● www.oxfordrestaurantguide.com

● www.visitoxfordandoxfordshire.com/see-and-do/Eating-and-Drinking.aspx