This city is a multi-course meal for visitors

By Don Heimburger

Photos by Don Heimburger and Leipzig Tourism Office

If you were to spoon out Leipzig and put it on a plate, you’d discover a salad, a main meat course, vegetable course, a sorbet interlude and a delicious dessert.

I’d designate the salad course as the city’s unusual green belt at the Auenwald; the meat course is the art, architecture and music; the vegetable course Martin Luther and the Peaceful Revolution; the sorbet interlude is this town’s love of coffee; and the dessert is the city’s zest for living and its nightlife.

The city of Leipzig in central Germany, population 500,000, has a colorful history stretching back more than 800 years, and many events have shaped this former East German city. The city’s people and several major historical events have fashioned this town, and made it what it is.

SORBS FIRST SETTLED HERE

Sorbs first settled here in the 7th century, establishing a trading post known as Lipzk or “place near the lime trees.” After Leipzig was granted a town charter and market privileges around 1165, it quickly developed into an important center of commerce.

Maximilian I decided to award Leipzig imperial trade fair privileges in 1497, which helped turn the city into one of Europe’s leading trade fair centers, and it remains so today. Following the world’s first samples fair held in Leipzig in 1895, the city remained one of the global trading hubs until World War II put a hold on that.

It’s hard to believe, but Leipzig has a floodplain forest that runs straight through its center, one of the largest of its kind in Europe. Consisting of eight square miles of trees, every year more trees are planted, and the green space is enlarged. A variety of protected plants and animals are found here, including a rare butterfly species.

This “salad area” or greenbelt is easy to spot on a roadmap, with a large green area running north to south through the city. Four streams also flow through the city. Another part of the city that has been “greened up” is the Leipzig Zoo, where tropical Gondowanaland just opened. This lush section of the zoo, larger than two football fields, allows visitors to come into close contact with the tropical rain forests of Africa, Asia and South America. It features 40 exotic animal species and approximately 500 different plant and animal species, and more than 17,000 plants started their journey in nursery gardens in Thailand, Malaysia and Florida to create this tropical environment.

MAIN COURSE: ART-ARCHITECTURE AND MUSIC

As Leipzigers are fond of saying, for the young and creative Leipzig is no longer an insider’s tip. Word has spread that the city’s working and living conditions are just right, and three universities with an artistic or cultural profile, as well as Leipzig University, constantly feed the pool of ideas. Leipzig is known for its vibrant arts, music and festival scene; this place not only appeals to artists and actors, but is also becoming a trendy destination for leisure travelers.

Leipzig’s dynamic art scene enjoys an excellent reputation worldwide. Interestingly, a former cotton mill, Spinnerei, in the trendy Plagwitz district, is home to a number of galleries and studios. Formerly the largest cotton mill in continental Europe, Spinnerei now has the highest density of galleries in Germany. In this old factory complex are 80 artists, 14 galleries and exhibition spaces which house creative professionals like architects, designers, craftspeople, retailers and printers.

Artist and professor Neo Rauch of the New Leipzig School, whose paintings combine his personal history with the politics of industrial alienation, reflects on the influence of social realism. Hollywood star Brad Pitt recently purchased one of his works.

The GRASSI Museum of Applied Art, with its world class collection, opened as Germany’s second museum of applied arts in 1874. It is considered one of Europe’s leading museums of arts and crafts. The high point of the year within the GRASSI museum’s special exhibition is a trade fair for applied art and design, an international forum of contemporary applied art and experimental design.

Then there’s another part of the Grassimesse, the Designers’ Open, which is a well-established independent design festival. An extensive program including lectures, workshops, movies and fashion shows complete the fair.

In 1996 the Leipzig Fair’s new exhibition complex opened, featuring trailblazing architecture, spacious avenues and the stunning Glass Hall at its core.

THE CITY OF MUSIC

If you go to Leipzig, a visit to St. Thomas’s Church is a must, since it is the home of the world-famous St. Thomas Boys Choir and where Johann Sebastian Bach was employed for 27 years as organist and choirmaster.

His grave can be seen in the chancel. Motets are performed every Friday and Saturday by the choir, and there are concerts in front of the statue of Bach outside in July and August. The Bach Museum is located opposite the church.

Another regular musical highlight is the Sunday recitals at Mendelssohn House. Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy used to live in the building, which now contains the only museum dedicated to the composer.

There are two additional important centers of music in Leipzig: the Leipzig Opera House and the Gewandhaus Concert Hall.

The Gewandhaus Orchestra, dating back more than 250 years, regularly performs in both venues. The Opera House is the third oldest civilian music theater stage in Europe. And Schumann House is dedicated to the memory of Robert Schumann, one of the greatest composers of the 19th century Romantic era.

Leipzig also hosts several music festivals, large and small, including the International Bach Festival, the A Capella Festival, the Leipzig Jazz Festival and the Mendelssohn Festival.

MARTIN LUTHER AND THE PEACEFUL REVOLUTION

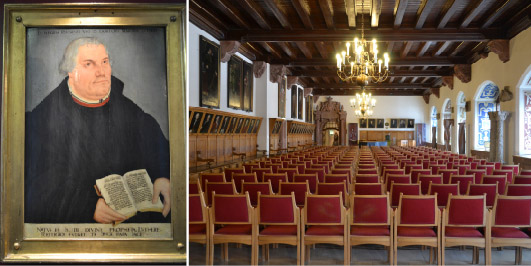

Our vegetable course includes reformer Martin Luther, who was known to come to Leipzig to face the Catholic Church hierarchy to explain his ideas about Christianity and indulgences. Martin Luther, who lived in nearby Wittenberg, stayed in Leipzig on no less than 17 occasions. His most important visit was for his participation in the Leipzig Disputation, or series of debates, held in Pleissenburg Castle in the summer of 1519.

After Duke George died, the Reformation was introduced in Leipzig in 1539. On August 12, 1545 Luther inaugurated the former Dominican monastery church of St. Paul’s as a protestant university church.

Leipzig was particularly significant in the rise of the Reformation movement, because Luther’s writings and numerous evangelical hymn books were distributed in large numbers from this city of printing shops and publishing houses. In Melchior Lotter’s printing shop alone, between 1517 and 1520, more than 40 works written by the great reformer were published.

In the Grafisches Viertel or Graphics Quarter of the city, the publishing industry flourishes. In 1912, 300 printers and nearly 1,000 publishing houses and specialized book shops, as well as 173 bookbinders, operated in Leipzig.

Leipzig is also known for helping overcome the GDR government. St. Nicholas Church—the oldest and biggest church in Leipzig—rose to fame in 1989 as the cradle of the Peaceful Revolution. Services for peace were and still are held there every Monday, and the following demonstrations at the end of the 1980s toppled the East German government, paving the way for German reunification. In the church, note the interior columns: they are designed to resemble palms.

A few other important sights to see in the city include:

- The Monument to the Battle of the Nations—the tallest monument in Germany—was erected to commemorate those who fell during the Battle of the Nations (also known as the Battle of Leipzig) fought against Napoleon’s forces in October 1813.

- In the Battle of the Nations, Austrians, Prussians, Russians and Swedes fought —500,000 soldiers in all— the biggest battle ever in world history, marking the decisive turning point in the war of liberation from Napoleonic rule.

(left to right) Battle of the Nations Monument; Porsche Leipzig Headquarters

The Mädler Passage, for centuries the city’s most exclusive arcade (one of 30 arcades in the city), is home to the famous Auerbachs Keller. Serving wine since 1525, this tavern/restaurant was immortalized in Faust by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the father of German literature.

YOUR SORBET IS SERVED

The café-cum-restaurant Zum Arabischen Coffe Baum is one of Europe’s oldest coffee houses (dating from 1694) and it used to number composer Robert Schumann among its regulars. Today the coffee museum on the third floor of the building contains 500 exhibition items on the history of coffee, the Saxons’ “national drink.”

- The Old City Hall, one of the finest Renaissance buildings in Germany, can be admired on the Market Square; it houses the Museum of City History. Inside is Katharina von Bora’s (Martin Luther’s wife) wedding ring and a pulpit in which Luther preached.

Town Hall Museum where a number of Martin Luther artifacts are exhibited.

NIGHTLIFE ABOUNDS

If you happen to be a night person, there is plenty to do in the evening, with all the city’s theaters, concert halls, variety shows and casinos. There are several dining and nightlife districts as well, such as Drallewatsch, Schauspielviertel, Südmeile, Münzgasse, Gohlis and Plagwitz. And when you arrive in one of the many clubs or bars, you’ll learn that often the term “closing time” is not in the vocabulary. There are 1,400 pubs and restaurants in this city, so dessert is not a problem.

And there you have it: a complete Leipzig meal with all the courses. Emperor Maximilan I knew something in 1497 when he granted the town imperial trade fair rights. He knew that one day Leipzig would be a multi-course city, and he was correct.

Auerbachs Keller Restaurant, located below the Mädlerpassage, is the best known and second oldest restaurant in Leipzig, described in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play Faust I, as the first place Mephistopheles takes Faust on their travels. The restaurant owes much of its fame to Goethe, who frequented Auerbach’s Cellar as a student and called it his favorite wine bar.

For more information, go to www.leipzig.de, www.leipzig.travel, or www.germany.travel

Hotel Fuerstenhof

An upscale Leipzig tradition

Not far from the main train station in Leipzig is the Hotel Fuerstenhof, a five-star gem with marble, gold-rimmed archways, high ceilings and soaring windows.

At one time a classic patrician’s palace, the 92-room air-conditioned hotel with 12 suites, features myrtle wood furniture, marble bathrooms and a friendly, dedicated staff. The staff is geared to making your stay a pleasant one, knowing your name when you come to the registration desk for questions, and providing service with a smile. I had more than a few special requests from the staff which were quickly and pleasantly taken care of.

There’s an indoor 7,000-square-foot pool area, equipped with saunas, fitness room, solarium, cosmetic and massage stations. Also, the hotel features a nice piano bar area with comfortable, plush seats, and tables, fine dining in the 18th-century style neo-classical Villers restaurant (with a choice of more than 200 wines), a complete breakfast area and a wine bar round out some of the amenities of this hotel.

The hotel was first mentioned in 1770 when Karl Eberhard Loehr, a banker, lived in the palatial home, built between 1770 and 1772. It was called the Loehr Haus. It opened as a hotel in 1889, and underwent a complete renovation and restoration in 1993. It is part of the Luxury Collection of Hotels, one of 62 worldwide luxury hotels.

For more information, go to www.hotelfuerstenhofleipzig.com/en