Hunting truffles in the Dordogne

By Marilyn Heimburger

Photos by Don Heimburger

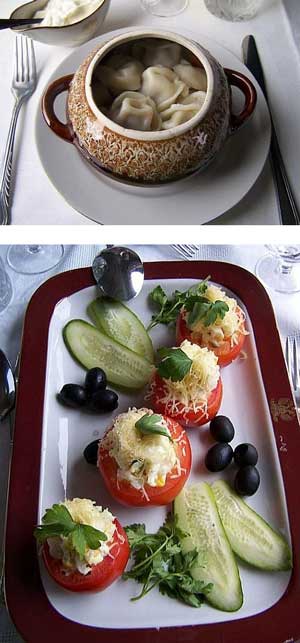

Dining in the Dordogne most certainly brings opportunities to pair wine with the other specialties of the area: foie gras, strawberries, walnuts and truffles.

In fact, the Perigord is known for producing the very best black truffle, an aromatic fungus resembling a small black potato. To experience this local treasure, I spent a delightful morning at Truffiere de Pechalifour, the truffle farm of Edouard Aynaud, learning the art of truffle hunting.

After meeting the high-energy Edouard, we entered a glass-doored, yellow stone building, where Edouard snaps open the lid of a large plastic bowl holding several black truffles, and thrusts it in my face. “Smell this,” he says in French, insisting that once you have this scent in your head, you’ll never forget it.

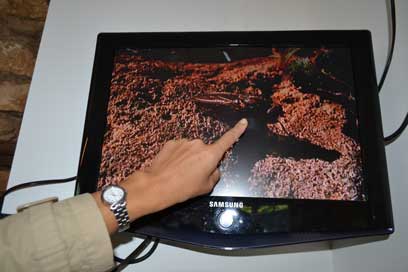

Edouard’s truffle-sniffing border collie

The valuable black truffle, sometimes called the Black Diamond, can command 1,000 Euros per kilogram, since the demand is always greater than the supply. Our host holds up a kiwi-sized truffle and we play “how much is this truffle worth?” My husband wins with his guess of 10 Euros, when the small scale records the truffle’s weight as 10 grams.

Now the lesson begins: truffles grow at the base of oak and hazelnut trees. The spores of the truffle form a web of mycorrhizal filaments that permeate both the soil and the roots of the trees. These filaments help the trees obtain nutrients from the soil, and in turn, the trees provide the truffle with needed sugars. Once this network spreads, there is a telltale brown circular area around the base of the tree called a “burn.” In the wild, this symbiotic relationship occurs with luck.

Here on the 10-acre Pechalifour farm, Edouard’s father planted his first trees in 1968. Today new tree seedlings with truffle spores grafted onto their roots are planted in the hopes of increasing the truffle crop. Edouard holds up a 2-foot-tall oak seedling to illustrate, and tells us that you must plant it and pray, and maybe in several years (3? 6? 10?) the telltale “burn” will appear. He explains that sadly, not many young people are getting into this business because it requires so much patience and optimism.

Edouard, however, personifies optimism and joy, explaining his craft in rapid-fire French (admirably translated by our local guide) and punctuated with animated facial expressions and gestures worthy of Marcel Marceau.

Once the “burn” is identified, there are three methods to locate the truffles beneath it:

- With a pig. Grinning, Edouard holds up a Cracker-Jack-toy-sized pink plastic pig to illustrate. Furthermore, he continues, it must be a female pig. Why? Because the truffle scent mimics that of a male pig sex hormone.

- With a stick. Now he whacks a slender willow stick several times across the length of the table. Tapping a stick around the area of the “burn” disturbs a little brown fly that likes to lay its eggs on a ripe truffle, so that its larvae can feed on the nutrients. A short video illustrates that the fly’s brown color renders it invisible at rest. But once disturbed, the fly will rise up and then return to the location of the truffle, which must be harvested before the egg-laying, larva-eating process begins.

- With a dog. The dogs must be trained while they are very young to recognize and search for the truffle scent. For that, Edouard uses the plastic film containers used before the age of digital photography. He pokes holes into the container and fills it with cotton that has been moistened with truffle oil. Then for one week he plays fetch with his canine student, rolling the container a little distance away, and rewarding the pup with treats and love when the prize is returned. The next week he hides the container in corners or behind something, and again rewards its return with treats and praise. The third week he buries the container outside under a little bit of soil and waits three days so that it no longer carries his human scent, but only the scent of the truffle, before sending the dog to find it. At the end of three weeks, with lots of praise and treats, the dog is trained.

Suddenly we are aware of a yellow labrador and a young black and white border collie snuffling around our feet, obviously eager to get to work. Edouard grabs a basket, some dog treats and a digging tool, and assuring us that he did not hide truffles ahead of time for us to find, we begin our spirited trek though the trees.

Walking slightly ahead of us, Edouard sees the telltale “burn” around the base of a tree, and gives his dog the command. Within seconds, the dog sniffs and puts his paw on a spot. Edouard scoops up a handful of the moist soil and sniffs it, crowing gleefully when he detects the scent of the hidden truffle. He pushes into my hands the special two-sided truffle-digging tool: pointed pick at one end, flat scraping blade at the other, and tells me to dig — but gently! We’re not digging up potatoes!

Soon my delicate poking isn’t fast enough for him and he rakes his fingers through the mud until he isolates the prize. After pointing to exactly where I should look, he lets me make the final discovery. Voila! There it is — and it’s tennis-ball HUGE! But, alas, it is spoiled inside because of the recent unfavorable weather. Edouard rewards his dog with a treat and a cuddle, and then crushes the truffle with his fingers and reburies it on the spot, so its spores can sprout again.

The best months for harvesting ripe truffles in the Perigord is December, January and February, and then only if the weather conditions have been favorable — too much rain and they grow too fast and don’t ripen at the right time. All in all, it’s a business that needs luck — and lots of dog treats.

www.truffe-perigord.com