A Mix of Symbolism and Satisfying Taste

by Sharon Hudgins

When the Easter season approaches, European kitchens are filled with the yeasty aromas of freshly baked breads, as cooks all over the Continent prepare the special loaves and buns traditionally associated with this important religious holiday.

In the past, devout Christians observed a strict fast during Lent, the six or seven weeks before Easter, when they abstained from eating animal products of any kind: red meat, poultry, milk, butter, lard, cheese and eggs.

In some parts of Europe, even sugar, honey, olive oil, and certain kinds of fish were on the list of forbidden foods. When Easter finally arrived, people celebrated with a huge meal featuring dishes made from all the ingredients that had been prohibited during Lent. Even though few people follow such strict fasts today, the tradition of feasting on special foods at Easter is still an important part of many European cultures.

Rich, yeast-raised breads full of milk, butter and eggs are an essential element of the Easter meal in most European countries. Often the breads are made in symbolic shapes and elaborately decorated with sugar icing, candied fruits or colored eggs. Homemade or bakery bought, these breads represent a continuity of traditions from centuries past, including much earlier, pre-Christian times.

Different countries, regions and towns of Europe have their own characteristic breads baked especially for Easter. In some places, these special breads are taken to church to be blessed at the Easter midnight mass or the Easter Sunday morning service, before proudly being displayed on the festive dinner table at home. And in Russia and many Eastern European countries, the table also has a little three-dimensional lamb modeled out of butter, for spreading on the bread after it is cut.

GERMANY AND CENTRAL EUROPE

Bakers in Germanic communities make Easter breads in a variety of shapes, secular and religious. Breads shaped like rabbits, lambs, baby chicks and fish are symbols of springtime, fertility and birth. Braided loaves—long and straight, round or wreath-shaped—are made with three strands of dough representing the Holy Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Germans and Austrians make several versions of Osterzopf (Easter braid), Osterkranz (Easter wreath or crown), and Striezel (stacked braided bread), as well as Osternester (Easter nests) or Eier im Nest (Easter-egg nest) with white or colored hard-boiled eggs surrounded by the dough. The circular braided Osterkranz is also symbolic of Christ’s crown of thorns, and the red-dyed eggs decorating many Easter breads are said to represent Christ’s blood and resurrection—although the egg’s significance as a symbol of rebirth and regeneration actually dates further back in time to the pre-Christian era.

Other special Germanic Easter breads include the Osterfladen—a flat, rectangular bread with a sweet filling of apples, raisins and almonds—and several varieties of Osterbrot (Easter bread) flavored with raisins, currants, candied orange peel, grated lemon zest, anise and cardamom. The Osterkarpfen (Easter carp) is a bread shaped like a fish, glazed with white icing, and studded with sliced almonds to represent fish scales. Germans also make Osterkorbe breads formed like Easter baskets and rabbit-shaped Osterhasen breads, all of them holding real or candy eggs. And the Eiermännle (Little Egg Man) is a flat bread shaped like a boy or man, with an unshelled hard-boiled Easter egg baked in the center of his body or inside a basket that he carries on his back.

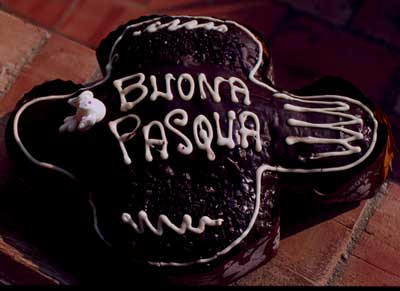

Lamb-shaped cakes and breads can be found at Easter-time from Alsace to Austria, from Germany to the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary. Baked in three dimensional metal or pottery molds, these represent Christ as the sacrificed Lamb of God, although their origin can probably be traced to earlier, pre-Christian rites in which baked dough effigies of sacrificial animals were substituted for live animals. Lamb breads are made from the same kind of sweet, yeast-raised doughs used for Alsatian Kugelhopf, Austrian Gugelhupf,and Polish baba (or babka). The cake versions are made from a simple white cake batter, although both chocolate and marble (mixed chocolate and white) lamb cakes sometimes show up in the flocks of Easter lambs sitting in bakery windows at this time of year.

The simplest lamb breads and cakes are merely dusted with a coating of confectioners’ sugar or drizzled with a light glaze of sugar icing. More elaborate cakes are covered with fluffy white frosting, sometimes garnished with shredded coconut, or spread with chocolate icing decorated with white icing swirls. The eyes are made from raisins, whole cloves, or coffee beans, and a small silk ribbon, often with a tiny bell attached, is tied around the lamb’s neck. Many of these lambs also hold a colored foil banner bearing the emblem of a lamb or a cross—recalling similar banners carried by Christian crusaders to the Holy Land a thousand years ago.

ITALY

Italy offers a rich variety of regional Easter breads, including Genoa’s pane dolce (sweet bread) full of raisins, candied fruit peel and pine nuts; Umbria’s cylindrical, cheese-flavored crescia; Venice’s large fugassa di Pasqua buns; and Cesenatico’s ring-shaped ciambelle, seasoned with anise and lemon peel. In Sicily, the edible centerpiece of the Easter meal is a large yeast bread shaped like a crown, with colored hard-boiled eggs embedded in the top. In some parts of Italy an old custom is still followed when Easter breads are made: the shell of the first egg put into the dough is cracked on the head of a young boy—supposedly to keep bad luck at bay.

The Easter bread most popular throughout all of Italy is a specialty originally from Lombardy—the columba di Pasqua (or columba pasquale), a sweet yeast bread full of candied orange peel, raisins, and almonds, made in the shape of a dove. Some of the fancier columbe have pockets of orange- or champagne-flavored pastry cream inside. Others are made with swirls of light and dark (chocolate-flavored) dough, like marble cakes. The plainest ones are garnished with only a simple sugar glaze, but the more elegant columbe are elaborately decorated with almond paste, white or pastel icing, chocolate, nuts or sugar-paste flowers.

(bottom left and right) Italian Easter dove cakes (columbe di Pascua) are a symbol of springtime, the Holy Spirit, and peace.; Italian cheese-flavored crescia loaves for Easter, at a bakery in Umbria

GREECE

Maundy Thursday, three days before Easter, is the time when Greeks bake their holiday breads. Known as tsoureki or lambropsomo, these sweet, eggy breads are traditionally flavored with mahlepi, an unusual spice made from the finely-ground seeds of a type of cherry. Other Greek bakers add mastikha, pulverized crystals of sap from mastic shrubs that grow on the island of Chios. Cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom and allspice can also go into the dough, as well as orange and lemon peel.

Greek Easter bread is made in different shapes from one region to another: a long braid, a braided wreath, a round loaf with bread-dough decorations on top in the form of leaves, flowers or a Byzantine cross. Each shape has its own symbolism. The three strands of braided dough represent the Holy Trinity. Wreaths and rings not only recall Christ’s crown of thorns but are also pre-Christian fertility symbols. Round shapes represent the life-giving sun, rebirth and resurrection. And no Greek Easter bread would be complete without one or more red-colored eggs—customarily dyed on Maundy Thursday—pressed into the top before baking.

SPAIN

The Spanish corona de Pascua (Easter crown) is another bread whose shape and symbolism is similar to Easter breads in many Mediterranean countries. Made from a sweet yeast-raised dough, the corona de Pascua is flavored with raisins, almonds, candied fruit peel, lemon and olive oil. Three strands of dough are first braided together, then formed into a ring. Whole, hard-boiled eggs are nestled into the top of the braid, usually one egg for each member of the family. Some people leave the eggshells white; others dye them red or a variety of spring colors.

Another Spanish Easter bread known as monja (nun) probably got its name from the nuns who traditionally baked breads, pastries and confections to sell from behind their convent walls. This orange-flavored bread—much like ones also found in Greece, Macedonia and Bulgaria—is round in shape, with a cross made of bread dough on top and four red-dyed eggs embedded at each point of the cross.

In the Castile region of Spain, Easter is celebrated with a large round loaf of bread in which shelled hard-boiled eggs, diced bacon,and chunks of Spanish sausages were imbedded in the dough before baking. And at Easter-time in some parts of Spain, godparents give their godchildren tortas de aceite, small savory buns made from yeast dough seasoned with orange, anise, and olive oil, with a single hard-boiled egg nestled in the center.

RUSSIA AND UKRAINE

Since Easter is a springtime celebration of new life, it’s not surprising that many traditional Easter breads are made in the form of ancient fertility symbols. The most graphic of these are the tall, cylindrical breads with a puffy dome on top, whose phallic symbolism is unmistakable. Festive breads of this shape are made in both France and Italy, but the most famous is Russia’s kulich, a saffron-scented yeast bread flavored with raisins, almonds and candied fruit peel. The domes are frosted with white icing that dribbles down the sides in a further reinforcement of the fertility image. The kulichi can also be decorated with colored sugar sprinkles or candied fruits, and a long thin red candle is usually stuck into the top of the dome. On Easter, Russian Orthodox churches are often filled with these special breads, their candles lighted, awaiting blessing by the priest.

Velikodnia babka is the Ukrainian version of this tall, yeasty Easter bread, with raisins, almonds and candied peel kneaded into the dough. Another traditional Ukrainian Easter bread is velikodnia paska, made from a rich yeast dough containing plenty of butter, sugar, and eggs, and shaped into large rounds. The tops are fancily decorated with ornaments made out of dough, usually with a cross as the center motif surrounded by elaborate swirls, small birds, leaves,or flowers. Perekladnets is a special, colorful Easter treat, a kind of coffee-cake loaf made with lemon-scented yeast dough and three different layers of filling: chopped dried peaches or apricots with candied fruits; chopped figs, dates and walnuts; and chopped almonds with candied cherries.

GREAT BRITAIN

Hot-cross buns are the most typical Easter bread in Great Britain. Baked on Good Friday, these round, slightly sweet buns often have chopped fruit peel and currants, raisins or sultanas in the dough. A cross is cut into the top of each bun before baking, or a strip of dough is used to make the form of a cross on top, to keep away evil on this sad day of remembering Christ’s crucifixion.

In some parts of Britain, a hot-cross bun is hung up in the house to keep away bad luck (fire, theft, illness) until Good Friday of the following year. Buns are also hung in the barns to protect the grain from rodents. As in the rest of Europe, these British hot-cross buns are an example of the powerful symbolism of breads baked for the Easter season.