Story and photos by Alison Ramsey

There’s something irresistible about German bakeries—the fresh brötchen and Berliners, croissants, and the bold espresso you can order alongside—something that makes it feel okay to stop at various locales throughout the day, even beyond just a morning coffee and pastry. It seems that a thick slice of cake and a mug of strong, steaming coffee any time of day makes a whole lot of sense when you’re in a region with such a rich baking history. Dresden, the capital of Saxony in Germany, and nearby Meissen and Leipzig have much to offer snack lovers when it comes to pastries and cakes. So pour a fresh cup, heat up a bun, and read all about the role Saxony played in the rise of gluten-filled goodness.

The five locations of Kandler Konditerei in Leipzig are always stocked with sweet temptations.

Russisch Brot

During the late 19th century, Dresden-based master baker Wilhelm Hanke adopted the 1845 St. Petersburg, Russia, recipe for Russisch Brot (Russian bread), which are crunchy glazed cookies made from sugar, egg whites, water, and flavoring, and formed into the shapes of alphabet letters. These are sold under the Dr. Quendt label and remain a popular Christmas treat or a delicious snack to help teach reading. The letters “M” and “W” are too fragile to be stable, so Dr. Hartmut Quendt ensured bags contain mirrored 1’s that snackers can use to create their own “M” and “W” shapes. It’s clear permission to play with your food!

Stollen

Dresden is also the birthplace of the authentic stollen Christmas cake—the Dresdner Christstollen. When stollen was first baked in the 1400’s, under the supervision of the church council, the bread was not allowed to contain butter or milk during Advent, so it was a dry and bland pastry consisting of flour, yeast, oil, and water. Ernst of Saxony and his brother Albrecht appealed to the Pope and asked that the dairy ban be lifted, so they could replace the oil with butter, as butter was cheaper than oil at the time. The appeal was denied, but finally, five popes later, Pope Innocent VIII sent Dresden the famous 1491 “Butter Letter,” in which he granted permission for dairy ingredients to be used in the stollen—although the Dresden bakers must, in return, pay a fine to be used toward the building of churches.

In 1730, Augustus the Strong, a stollen lover, commissioned a group of 100 Dresden bakers to bake an almost 4,000-pound loaf, which was brought to the king’s table using eight horses. A giant oven was built especially for this occasion, and an oversized knife was designed specifically for the event. This is the basis for the annual Dresdner Stollenfest (or “Striezelmarkt”), which takes place in Dresden the Saturday before the second Sunday in Advent. The festival is a highlight of the pre-Christmas season and celebrates the stollen baking tradition, featuring a colorful parade and the sale of varieties of stollen.

A huge stollen is still made annually and divided into smaller pieces on a specially shaped stollen cutting board—using a 26-pound replica of the original baroque knife from the Residenzschloss (Royal Palace) Court Silver Collection of Augustus the Strong—with cake portions sold to raise money for charity. The Stollenfest knife design features a swooping stainless-steel blade and Augustus the Strong’s coat of arms and rose tendril.

Left: A Dresden bakery displays its stollen seal. Right: This life-sized figure of Augustus the Strong is displayed in the Dresden Residenzschloss.

Stollen has its own protected name and registered trademark, and the recipe needs to follow certain guidelines to earn the golden, oval “stollen seal.” The cake only passes the test for high quality and validity if it contains no margarine and no artificial flavors or preservatives. The Dresdner Stollen Association requires that each cake contain butter, rum-soaked raisins, candied orange peels and lemon peels, and sweet and bitter almonds to receive the seal. Outside of these requirements, the approximately 110 Dresden bakeries that produce this sweet each use their own secret spice mixture, passed down through generations, which results in varied and distinctive flavors from bakery to bakery. Each stollen is labeled with a 6-digit seal number, to identify and track the bakery of origin. Also identifiable by the European Union-protected geographical indication, true Dresdner Christstollen is marked with a blue and yellow Geschϋtzte Geografische Angabe (“protected geographical indication”) sticker. Dresdner Christstollen can only be produced within Dresden itself or within specific boundaries surrounding the capital. This cake is best enjoyed by removing slices from the middle and pushing together the ends, eating the cake from the center outward. It is seen as traditional Dresden “finger food,” with no need to use a fork.

Eierschecke

For something slightly sweeter, the Dresdner Eierschecke is a popular pastry choice. It’s a 3-layer confection consisting of a cake base topped with a custard-like quark cheesecake center, and a layer of sweet vanilla egg white on top, dusted with powdered sugar. Only found in Saxony and neighboring regions, this treat is often served with coffee or tea, and makes its way into celebratory menus for birthdays, weddings, and holidays. Some bakeries add chocolate, dried fruit, and sliced nuts, but the original recipe is simply the three-layered stack of varied texture.

Eierschecke and other traditional Saxon specialties are served at the Pulverturm.

Eierschecke is on the dessert menu at the Pulverturm restaurant next to the Frauenkirche. A historic vaulted powder tower containing portions of the original walls, Pulverturm delights guests with Saxon specialties, homecooked suckling pig, and rousing tableside performances by lively, costumed, character musicians. Be sure to try your hand at funnel-drinking here—a practice that stems from Augustus the Strong’s love of Saxon wines but his court’s dislike for washing numerous wine glasses. The court created a special funnel fit to Augustus’ mouth measurements, so servants could pour the wine directly through the funnel into his open mouth. At the Pulverturm, a variation on this method involves drinking herbed liquor from tiny funnels. Named “Cosel’s Tears,” the drink’s herbs were said to grow from the tears of Augustus’ former mistress, the Countess of Cosel, whom he banished to Stolpen Castle for more than 40 years because of her interfering interest in politics. After a satisfying Saxon meal, have a sugar-dusted slice of Eierschecke and cup of espresso to complete the full Pulverturm experience.

Pulverturm restaurant in Dresden is a full-service, medieval-themed entertainment and dining experience.

To make your own Eierschecke, try the recipe provided by Meissen porcelain manufactory underglaze painter Marlies Moser in the cookbook Cooking With Meissen. A 30-minute drive from Dresden, the Meissen manufactory creates fine porcelain vessels on which to serve tempting treats. At this company that labels its pieces with the forgery-proof “Crossed Swords” trademark, Moser worked for 40 years in production, painting underglaze onto unfired, porous porcelain—a skill that requires much training, a high level of precision, and years of experience—because the paint immediately penetrates and spreads, making later touchups impossible. The work of an underglaze painter is especially important for iconic Meissen designs like the 1731-created “Blue Onion,” whose luminous, metal oxide cobalt blue color only releases upon final firing. Moser now works in the demonstration workshop at the House of Meissen, and contributed her “Leutewitz Eierschecke” recipe for the company cookbook. Imagine a piece of this cake presented on a beautiful artisan-decorated Meissen porcelain dish!

The Meissen company cookbook features 24 recipes from appetizers to desserts. Saxon potato soup, Saxon meatballs, beef sauerbraten, quark dumplings with plum compote, and an inverted apple tart are among the list, and each submission includes a biography of the Meissen employee who contributed it. This beautiful, full-color hardbound book shows the food plated on fine porcelain tableware and includes sections about dining etiquette and the history of the craft.

Meissner Fummel

Eighteenth century legend tells that Augustus the Strong, who first commissioned the now-famous Meissen porcelain, used to send couriers back and forth between Meissen and Dresden with factory status updates. The town of Meissen is known for its excellent wine production (try the romantic, antique-filled Vincenz Richter wine restaurant!) and the couriers would often arrive back at the Dresden court intoxicated. Augustus’ solution was to instruct Meissen bakers to invent a pastry so fragile that it could remain intact only if delivered by a sober courier. The result was the hollow, brittle, extremely delicate Meissner Fummel cake, which had to be safely delivered to the Saxon Elector along with the progress reports about the porcelain. Made only with simple ingredients, Fummel is essentially a shell of flaky bread sprinkled with powdered sugar. Zieger Konditerei in Meissen produces this balloon-like baked good, which has been a protected geographical indication since 2000 and can only be manufactured in Meissen. The Fummel is often given to newly married couples in Meissen as a symbol of love’s fragility, and small gifts or cards are sometimes tucked into the center.

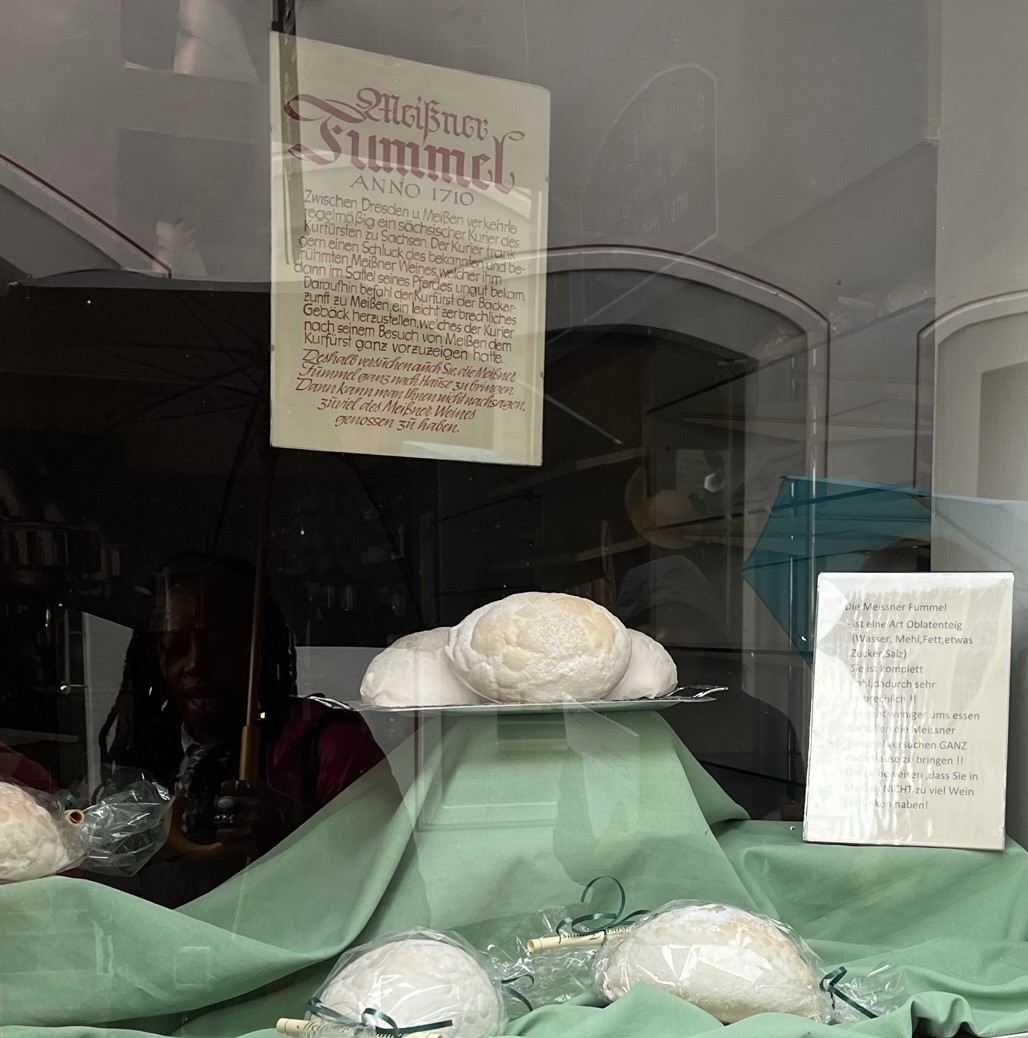

Left: A bust of Augustus the Strong appears in the interactive Zwinger Xperience, a multi-media immersion into the story of the baroque Zwinger building and festival area commissioned by Augustus. Right: This street window in Meissen displays loaves of Fummel along with a poster telling the humorous German story of why the bread recipe was initially invented.

You’ll be sure to fumble that Fummel after a few glasses of wine here! Vincenz Richter wine restaurant in Meissen celebrates its 150th anniversary this year. The 500-year-old building that houses hundreds of antiques and historical items is known as one of Germany’s most romantic places. The family winery produces its delicious wine varietals on the steep slopes of Meissen’s Elbe River valley.

Leipziger Lerche

The Leipziger Lerche (“Leipzig Lark”) dessert was born as part of the animal protection movement in the 19th century. Songbird larks used to be hunted and baked with herbs and eggs into a pastry crust and then served as a hearty delicacy. This culinary luxury was enjoyed in Leipzig and beyond, and many bird carcasses were bound in twine and shipped from Saxony to various countries around the continent for others to cook. The bird-baking business boomed, and the bird population declined. In 1876, after overhunting and a severe storm had killed off many of these birds, King Albert of Saxony banned lark trapping. To combat the suffering of this Leipzig business, some clever confectionaries in Leipzig then created a marzipan-stuffed shortcrust tart as a substitute for the traditional meat quiche. Now served in a small, fluted muffin cup, like a miniature pie, this baked good features two strips of dough crossed over the top to represent the trussing used to tie up stuffed larks. Beneath the ground almond and egg white mixture of the tartlet, there is often a cherry or dollop of jam to symbolize the heart of the lark. Kandler Konditerei in Leipzig is a popular source for “Kandler Lerche” pastries of this style, baked fresh daily and as naturally and preservative-free as possible, with numerous packaged options sold for a sweet, Saxony-specific souvenir.

Save a songbird and let Kandler Konditerei tempt you with a Leipziger Lerche.

For a tasty variation of Leipziger Lerche, try the ice cream version served at Auerbachs Keller in Leipzig. This bundt-cake-shaped mound of ice cream is seated on a petaled crust and topped with a dark chocolate medallion stamped with “Auerbachs Keller Leipzig” and an image of Dr. Faust riding astride a wine barrel. Goethe and Martin Luther were regular guests of Auerbachs Keller, and it’s a treat to dine in the historic basement rooms of the Mädler Passage where they sat and to eat traditional Saxonian cuisine, including this new take on a famous regional dessert.

Auerbachs Keller Leipzig serves a special iced Leipziger Lerche with curd-cheese-lime-mousse and raspberry sauce.

Auerbachs Keller in the Mädler Passage is the most famous and second oldest restaurant in Leipzig, and was one of the most popular places for wine in the 16th century.

| Visiting Saxony? Take an audio guided tour through the Meissen Manufactory and visit the Meissen Porcelain Foundation Museum. Enjoy coffee and delicacies at the Café & Restaurant Meissen, where your snacks are served on fine porcelain and you can sample the specially created Meissen cake featuring the crossed swords trademark. Register for a porcelain casting class or creative workshop and make your own Meissen masterpiece—available for adults and kids alike—or personalize a Meissen coffee mug and have your unique creation safely shipped directly to your home. Sign up your kids for an etiquette class to learn the art of fine dining or join a themed specialty meal (brunch with organ recital, Advent dinner, Christmas dinner, or Ladies Crime Night dinner). The one-hour “Women at Meissen” social history class highlights the significant role women have played in the manufactory’s workforce since the 18th century. The “Tea, Coffee, and Chocolate” event is offered once a month and teaches participants about the three “pleasure drinks” that were popular luxury goods during the Baroque period and how Meissen porcelain played a role in providing many varieties of elegant drinkware. |

Meissen porcelain tableware makes every cake look better. Sweets and special place settings are a suggested Saxony souvenir.